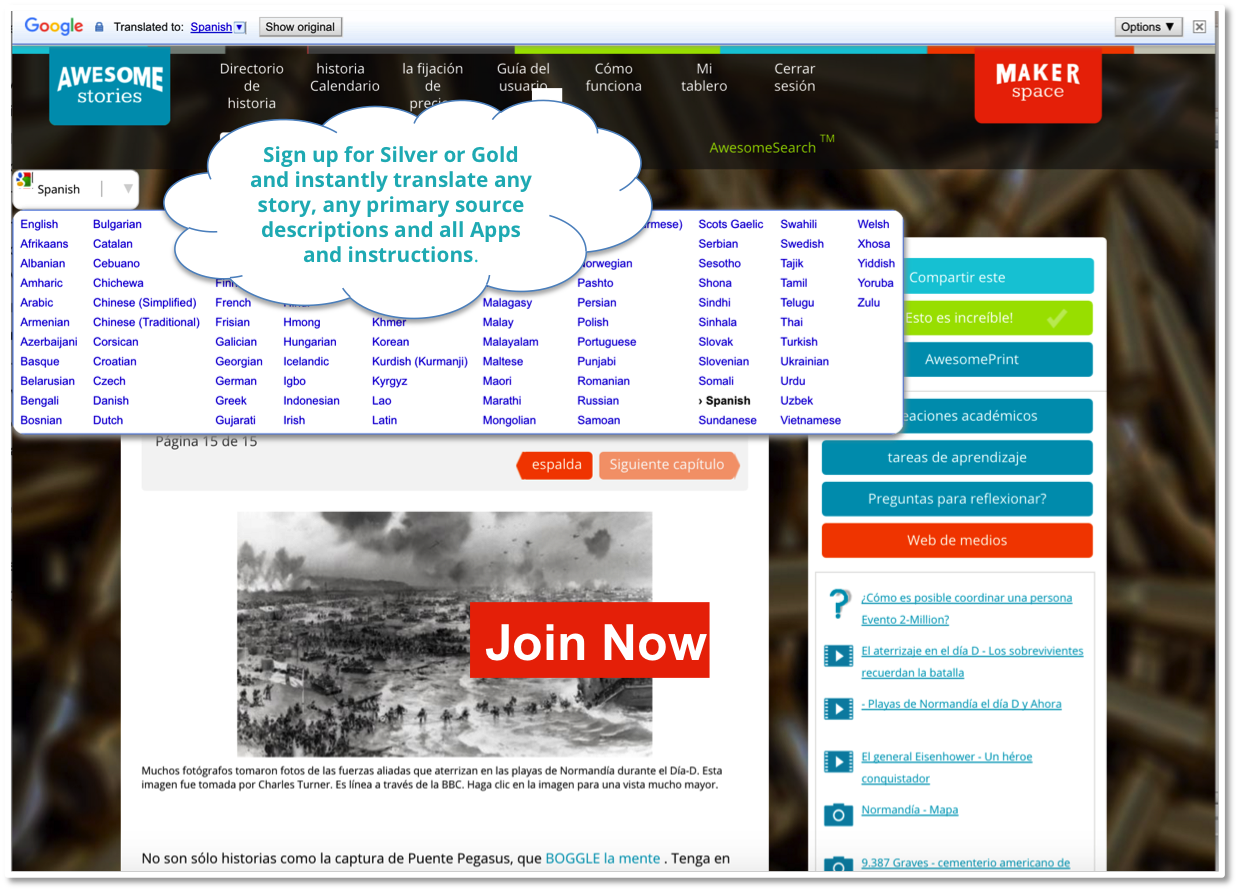

This illustration, created by Charles Raymond Macauley for the 1904 edition of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, depicts Gabriel Utterson as he searches for Edward Hyde. His patience is rewarded when, in the shadows, Utterson sees a man—likely Mr. Hyde—approaching the door of a building for which Hyde possesses the key.

As Mr. Utterson, the lawyer, narrates the strange tale of Dr. Jekyll, he recalls a task he once performed for his friend/client. Jekyll had asked Utterson to write his Last Will and Testament.

Something about that Will, however, has always bothered Jekyll’s lawyer—and—it has everything to do with Edward Hyde.

It has long been my custom, after dinner on a Sunday, to sit by the fire and read until the church clock rings out the hour of twelve, whereupon I take myself to bed. On this night, however, as soon as my meal was done, I went to my business room, where I took from my safe the Last Will and Testament of Dr. Henry Jekyll.

I sat down to study the document, groaning as I read these words:"I, Henry Jekyll, being of sound mind, do declare that in the event of my death or disappearance all my possessions should pass into the hands of my friend Edward Hyde and that the said Mr. Hyde should step into my shoes without delay and take my place as head of my household."

This document had long troubled me. I had, from the first, thought it madness for Jekyll to leave his fortune, his very substantial fortune, to a man unknown to me. But now, having learned something of Mr. Hyde, I was even more concerned.

Returning the Will to my safe, I put on my coat and set out for Cavendish Square, where lived my friend, the great Dr. Lanyon. If anyone knew about Jekyll, it would be him.

Lanyon’s butler ushered me into the dining room, where my friend sat alone over a glass of wine. Lanyon was a hearty, healthy, dapper red-faced gentleman, with a shock of prematurely white hair and a boisterous and decided manner.

We had attended school and college together, and had always thoroughly enjoyed one another’s company. At sight of me, Lanyon sprang from his chair to welcome me with both hands.

After a little rambling talk, I led up to the subject which preoccupied me so. “I suppose, Lanyon, that you and I must be Henry Jekyll’s oldest friends ...”

He chuckled. “I wish the friends were not quite so old but, yes, I suppose we are. I see little of him now, though.”

“Oh?” I said. “I thought you two shared a common interest, both being medical men.”

“We did once,” Lanyon sighed, “but we haven’t been close for more than ten years. He began to go wrong, wrong in my mind. Jekyll’s head is full of such unscientific balderdash. Far too fanciful.”

Ah, I thought, relieved, they’ve had a falling out only over some scientific matter. “I wonder,” I said, “if you’ve ever come across another, more recent friend of his, one Hyde?”

“Hyde?” repeated Lanyon. “No. Never heard of him.”

And that was all the information I carried home with me. That night I tossed and turned in my great dark bed until the small hours, besieged by uneasy questions and dreams. I saw a great field of lamps in a nocturnal city; the figure of a man walking swiftly; a child running; and then that human monster crushing the child down and passing on regardless of her screams.

The figure haunted me all night. And if at any time I slept, it was but to see it glide more stealthily through sleeping houses, or more swiftly and still more swiftly, even to dizziness, and at every street corner crush a child and leave her screaming.

This fiend had no face, or one that baffled me and melted before my eyes; and thus it was that there sprang into my mind a strong curiosity to behold the features of the real Mr. Hyde and see for myself what manner of man he was.

If I could but once set eyes on him, the mystery might lighten and perhaps roll away, as is the habit of mysterious things when examined closely. I might see a reason for my friend’s strange preference and for the startling clauses of the Will.

It would be a face worth seeing: The face of a man without mercy. A face which had but to show itself to inspire in people’s minds a spirit of enduring hatred.

I resolved, then and there, to return to that street of bright shutters and gleaming brass, and wait there till Hyde once again came to the door. If he’s Mr. Hyde, I thought boldly, well then, I shall be Mr. Seek.

I began to haunt the rear entrance of the house. In the morning, before office hours, at noon, when business was plenty and time scarce, at night under the fogged city moon, by all lights, at all hours, I was at my post.

And, at last, my patience was rewarded. It was a fine, dry night with a frost in the air. The street lamps, unshaken by any wind, drew a regular pattern of light and shadow.

By ten o’clock, the street was solitary and, in spite of the low growl of London from all around, very silent; so silent, indeed, that I heard the odd, light footsteps long before I saw the one who made them.

The steps drew swiftly nearer, and swelled out and suddenly louder as they turned the corner. I withdrew into the shadows to observe what manner of man I was to deal with. He was small, and very plainly dressed, and as he made for the door he drew a key from his pocket. I stepped out and touched him on the shoulder.

“Mr. Hyde, I think?”

He shrank back with a hissing intake of breath. But his fear was only momentary and, though he did not look me directly in the face, he answered coolly enough.

“That is my name. What do you want?”

“I see you were going inside,” I replied. “I am an old friend of Dr. Jekyll’s - Mr. Utterson of Gaunt Street - you must have heard my name. Meeting you so conveniently, I thought you might admit me.”

“Dr. Jekyll is not at home.” He spoke in a husky, whispering, somewhat broken voice. “Now how do you know me?”

“Why, by description. We have friends in common. Henry Jekyll for one.”

“He never described me to you. Why are you lying?” cried Hyde with a flush of anger.

“Come now,” I said, “this is not fit language between gentlemen.”

At this he gave a savage laugh, and lifted his head so that I saw him plainly for the first time. He was pale, with a displeasing smile and a murderous look in his eye. I felt, in an instant, a disgust, loathing, and fear such as I had never known. If ever I read Satan’s signature upon a face, it was on Mr. Edward Hyde’s.

“Perhaps it is as well that we’ve met,” he said. “You should have my address.”

He gave me a house number and the name of a street in Soho; and then, with extraordinary speed, he unlocked the door and disappeared into the house.

Badly shaken by the encounter, I walked round the corner into a square of ancient, handsome houses. I stopped and knocked at the door to Jekyll’s house which, as ever, wore a great air of wealth and comfort. The door was opened, almost at once, by the butler.

“Is Dr. Jekyll at home, Poole?”

“I will see Mr. Utterson.” Poole admitted me and went off to seek his master.

The large comfortable hall, warmed by a bright open fire, was one of my favorite rooms in all of London, but tonight there was a shudder in my blood. The face of Hyde sat heavy on my memory, and I seemed to read a menace in the flickering of the firelight on the polished oak cabinets and the uneasy starting of the shadow on the ceiling. I admit, to my shame, a feeling of relief when Poole returned to announce that Dr. Jekyll was out.

“Poole,” I said. “I saw a gentleman, a Mr. Hyde, enter by the old dissecting-room back door some minutes ago. Is that all right when Dr. Jekyll is not at home?”

“Quite all right, sir. Mr. Hyde has been given a key.”

“Your master seems to place a great deal of trust in that young man.”

“Yes, sir, he does indeed,” answered Poole. “The other servants and I have orders to obey Mr. Hyde at all times.”

“I do not think I have ever met Mr. Hyde here?”

“Oh no, sir. He never dines here,” replied Poole. “Indeed, we see very little of him on this side of the house. He comes and goes by the laboratory.”

I set off for home with a very heavy heart. Poor Harry Jekyll, I thought to myself, what has he got himself into? This Mr. Hyde must have secrets of his own, dark secrets compared to which poor Jekyll’s worst would be like sunshine. Things cannot continue as they are - if Hyde suspects the existence of the Will, he may grow impatient to inherit.

Back

Back

Next Chapter

Next Chapter

Back

Back

Next Chapter

Next Chapter