In 1976, Gueli Riabov, a Moscovite producer, visited Sverdlovsk (previously and currently known as Ekaterinburg) and the Ipatiev House (where the Romanov family had been executed).

It was not long before the house was demolished and, from the moment of his visit, Riabov wanted to find where the Tsar and his family had been buried.

During his youth, Alexander Avdonin (a geophysicist who was born in the town and was also interested in learning the whereabouts of the imperial family) had met one of the Romanov executioners, Piotr Ermakov. He’d also met other people with information about the family’s fate.

Riabov met Avdonin, and the two men began to talk about how they could find the missing bodies. A meeting with Alexander Yurovsky, the son of Yakov Yurovsky (the main executioner), was invaluable.

Alexander gave the two researchers a previously unpublished account which his father had written about the execution. Yakov had read his essay - a four-page document now known as “Yurovsky’s Note” - to a group of former local Bolsheviks during February of 1934.

According to his story, two days after the murders Yurovsky and his comrades were driving their truck with eleven bodies inside. The truck stalled near a level crossing, causing the men to think that perhaps they should bury the bodies in that area.

It would be their second attempt to dispose of the bodies since the first burial (at an abandoned mine known as the “Four Brothers”) was temporary. Yurovsky worried that people with information would tell their story. The risk was especially high since the White Army, comprised of pro-monarchists who opposed the Bolsheviks, was nearing Ekaterinburg.

According to his account, Yurovsky and a few comrades buried nine of the eleven bodies in one mass grave. Two other bodies were burned and buried nearby.

Within days after the murder and reburial of the family’s remains, Ekaterinburg did, in fact, fall to the advancing White Army. The Bolsheviks’ desire to kill the Tsar, and his family, was apparently motivated (at least in part) by concerns that the White Army would free the Tsar and restore him to the throne.

With the “White Russians” in charge of Ekaterinburg, Nikolai Alexeievitch Sokolov - a “White Russian” and monarchist sympathizer - was assigned to investigate what had happened to the Romanovs. Working as quickly as possible, so he could accumulate evidence in case the Red Army recaptured Ekaterinburg, Solokov visited the places involved in the murder.

At the Ipatiev House, he had bullets cut from the cellar-room walls. He visited the “Four Brothers” mine. He talked with individuals with apparent knowledge of events.

Able to leave Ekaterinburg before the town was recaptured by Bolshevik sympathizers, Sokolov managed to get himself, his family and his evidence out of Russia. He ended-up in France, settling in the town of Salbris (Loir et Cher), where he wrote a book about his findings. The work was published posthumously since Sokolov died soon after finishing his assessment.

Gueli Riabov had read Sokolov’s book (Enquête judiciaire sur l'assassinat de la famille impériale Russe) which included testimony (see Chapter 20) from a gate-keeper with some knowledge of the bodies’ whereabouts. (Sokolov’s archive of materials is now maintained at Harvard University.)

Armed with as much information as they could glean, Riabov, Avdonin and their searching friends found the temporary burial place, at Four Brother’s Mine. A wooden fence, which Sokolov’s investigators had previously installed, was still in place. So were other objects, including pieces of clothing.

The bodies, however, were not there.

Yurovsky’s Note gave the researchers more clues. When the executioners’ truck had been stuck in the mud, a local gatekeeper had provided wooden pallets to help free the truck. Drilling for samples near the level-crossing, where Yurovsky said the truck had stopped, Avdonin and Riabov found pieces of wooden pallets mentioned in Yurovsky’s account.

Discovery of the skeletons was now within reach.

On the 30th of May, 1979, Riabov and Avdonin excavated the wooden remnants plus the earth which covered them. At a depth of about .8 meters (2.62467 feet) they saw skeletal remains.

Finding three skulls, without much trouble, the men decided they should stop. What if someone saw them? After taking pictures of their discovery, including the skulls, they ultimately reburied the remains exactly where they had found them.

Then ... they kept quiet about their discovery. In 1979, the political climate in the Soviet Union was not conducive to revealing such news.

Ten years later, Mikail Gorbachev was leader of the USSR. He had instituted a system of openness (“Glasnost”) and economic reforms. Although Avdonin believed it was still too soon to reveal their findings, Riabov disagreed. He agreed to an interview, with a Moscow newspaper, then wrote his own article about the findings which was published in “Rodina,” a Russian-language magazine.

Riabov, however, did not disclose the exact location of the burial ground. In fact, he purposely stated that it was about 500 meters from where it really was situated.

Two years later, in March of 1991, Riabov convinced Boris Yeltsin to support recovery efforts of the skeletal remains. A team of people (including jurists, scientists and archeologists) began their work at the burial site.

On or about July 11, the team discovered around 1000 bone fragments but only nine skulls. However ... eleven people had been murdered.

This finding gave additional credence to Yurovsky’s Note since he’d stated that two people were burned separately. His account said those two individuals were Alexei and the maid, Anna Demidova.

On the 18th of July, 1991, the rest of the world learned about the sensational discovery. The recovered remains were initially placed in a secure location - the shooting stall of Verkh-Issetsk - so they could be studied.

Russian scientists, using photographic superimposition with evidence from the nine skulls, concluded that the bodies of Alexei and his sister, Maria, were missing. They believed they had identified the rest of the eleven people who were murdered, including Nicholas and Alexandra.

Another forensic team, led by Dr. William Maples (an American from the University of Florida), arrived at Ekaterinburg on the 25th of July, 1991. Maples and his team concluded that it was Anastasia’s body (not Maria’s) which was missing (together with Alexei’s). They analyzed dental and bone specimen to reach their conclusion.

During the summer of 1992, Pavel Ivanov (a specialist in DNA analysis) announced that he would conduct DNA tests on the bones by working with Peter Gill (from the British Forensic Science Service). Using bone samples from the nine recovered bodies, the two men and their teams conducted nuclear and mitochondrial (mt) DNA testing.

Surviving relatives of the imperial family - including Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh - gave DNA samples. When the investigators compared that DNA with the bones believed to be those of the Tsar (Nicholas II), they discovered an apparent anomaly (or mismatch).

To further investigate this development, experts exhumed the remains of Georgiy Romanov (the Tsar’s younger brother who had died of tuberculosis in 1899).

Georgiy’s DNA had the same feature (heteroplasmy) as the bones believed to be those of Nicholas II. Experts were thrilled with this discovery, concluding that the disease had likely died-out in later generations of the Romanov family.

In short ... team members were confident they had properly identified the remains of Nicholas II.

By July of 1993, Gill and Ivanov announced that DNA studies revealed the remains had a 98.5% probability of belonging to members of the executed Romanov family.

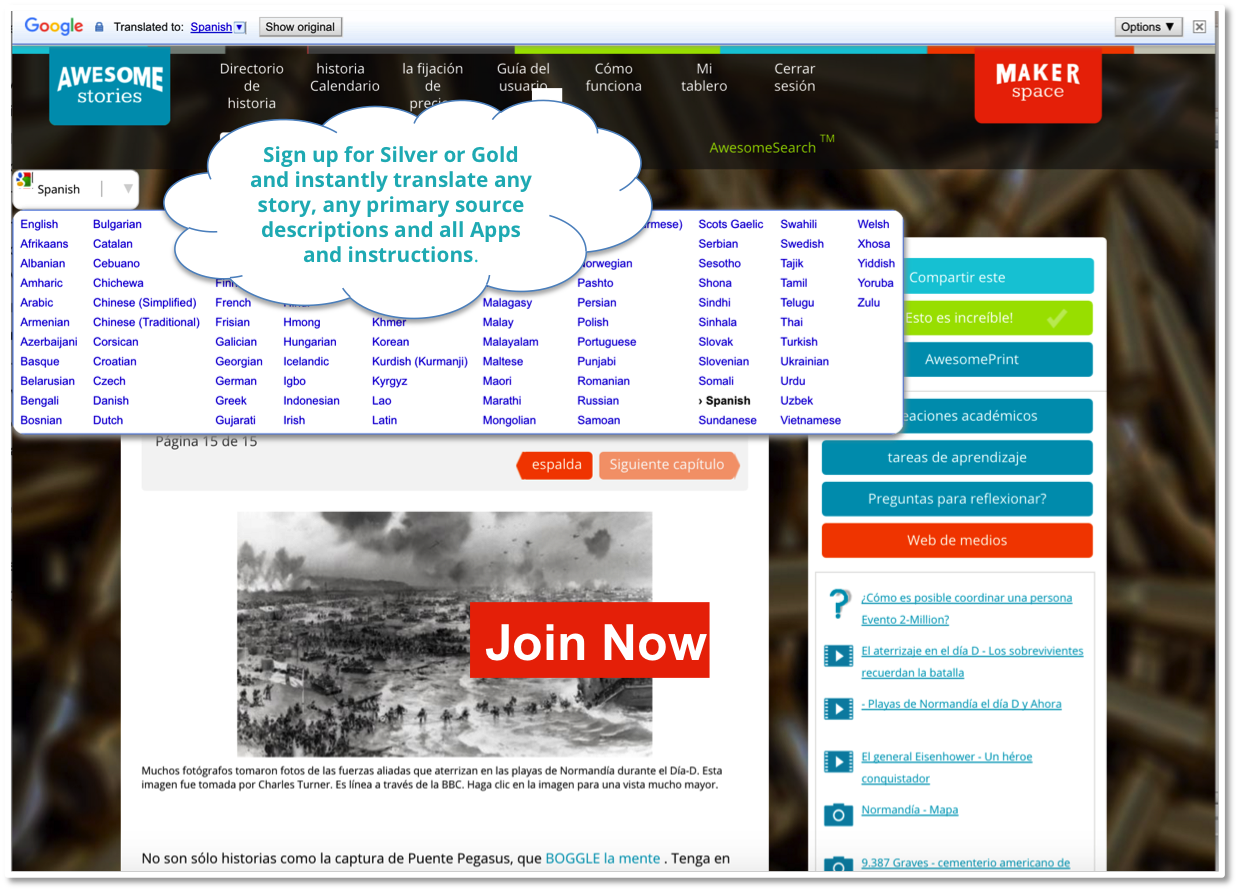

This image depicts Sokolov and members of his team at the Four Brothers' Mine, where the Romanov bodies were first buried. The specific location is where a second bonfire had been set by Yakov Yurovsky and his comrades.

Click on the image for a better view.

Media Credits

Image, from the Sokolov Archives, via a Russian-language website.