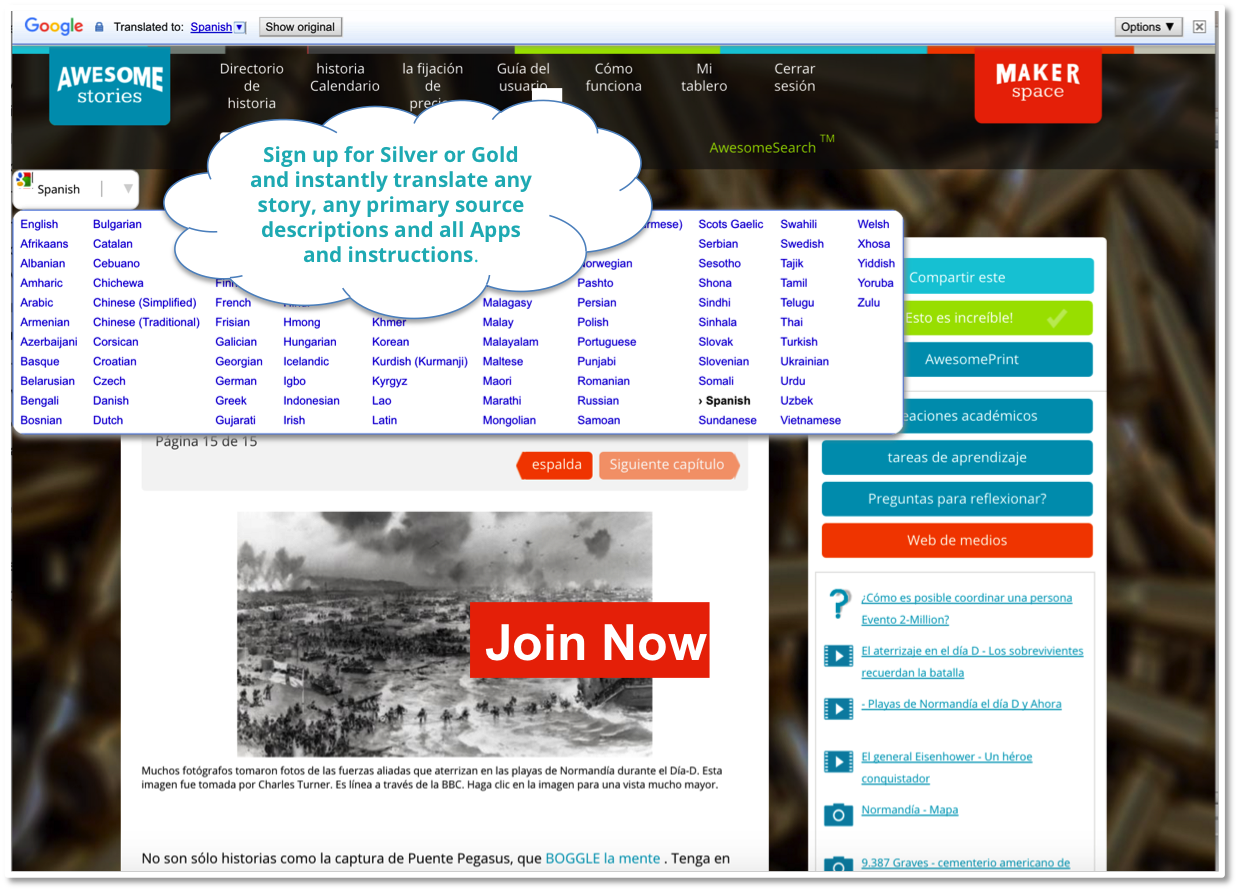

Members of the Sons of Liberty, a group organized to protest the Stamp Act, burn the law in Boston during August of 1765. Image online, courtesy Library of Congress.

What was the Stamp Act of 1765? It was a law, passed by Parliament, requiring American Colonists to use specially printed-and-embossed paper, produced in Britain, for their legal documents and newspapers.

Of course, it cost extra for Americans to buy such paper. The extra funds were actually a tax which the British government would collect and use as its leaders saw fit.

Beyond the type of watermarked paper to be used for legal documents and newspapers, the Stamp Act reached into nearly every aspect of a Colonial's life, including the purchase of dice and playing cards. Americans would have to purchase Stamps (in specific amounts, laid-out by Parliament) every time they purchased any item (and there were many) listed in the law.

A sheet of Penny Stamps has survived from the Stamp-Act era. Now owned by the British Library, it shows us the actual stamps which aroused such anger (including burning the stamps) among Americans.

The whole idea of the Stamp Act was less about earning money for Britain, via tax collection, and more about asserting Parliament’s power over the colonists. Curators at the Library of Congress give us a bit of background about the Stamp Act’s purpose:

Although the tax would not raise much money, the British chancellor of the Exchequer Sir George Grenville wanted a declaration of Parliament's sovereign right to tax the colonists.

Grenville’s plan backfired. Colonists were exceedingly upset when they were directly taxed, in a revenue-generating scheme, by a government in which they had no say. No Americans were elected as Members of Parliament, so why should Americans pay any amount of their income to the British government?

Soon after the law was passed, Benjamin Franklin’s newspaper-printing partner decided to ignore it. On the 31st of October, 1765, the Pennsylvania Gazette (Franklin’s paper) announced all issues were being suspended to protest the law (which required, among other things, that newspaper buyers had to pay a penny-per-page tax for masthead newspapers).

Immediately thereafter, David Hall (Franklin’s partner) released the news on plain, un-stamped sheets of paper. He replaced the papers’ masthead with these words: "No Stamped Paper to be Had." Hall was thus able to subvert the law, legally, while still supplying his customers with "the news."

In 1766, after Benjamin Franklin learned how angry the Stamp Act was making colonists in Pennsylvania, the famous American designed a cartoon to demonstrate how the law would likely harm Britain more than it would harm the Colonies. He called his creation “MAGNA Britannia, her Colonies REDUC'd” and printed the image on cards which he could hand-out to people.

In London during 1766, as Parliament debated whether to repeal the Stamp Act, Franklin distributed his cards to Members of Parliament. He wanted those lawmakers to understand the “Moral” of their actions in imposing a direct tax on the American Colonies:

The Moral is, that the Colonies may be ruined, but that Britain would thereby be maimed.

It wouldn’t do, for Britain to “be maimed,” and Parliament repealed the unpopular Stamp Act in 1766. To summarize its life cycle:

- Born (that is, passed by Parliament): March 22, 1765

- Burned (in Boston, among other places): August, 1765

- Died (that is, repealed by Parliament): March 18, 1766

Colonists enjoyed their apparent victory, figuratively holding a "funeral" for the Act which had a short, one-year life span.

Even if Parliament hadn’t repealed the unpopular Act, Colonists were intent on ignoring or subverting it. James Otis summarized one of the major reasons to oppose the law when he argued against it in Boston, during a town meeting in the spring of 1765:

...by [the British] Constitution, every man in the dominion is a free man: that no parts of His Majesty's dominions can be taxed without consent: that every part has a right to be represented in the supreme or some subordinate legislature.

In other words ... "no taxation without representation."

But Parliament wasn’t finished with its efforts in taxing Americans. The much-despised Stamp Act was soon replaced with equally onerous laws which continued to rile the Colonists.

ISSUES AND QUESTIONS TO PONDER:

Colonial Americans burned copies of the law, known as the Stamp Act, in very public places. What was the point of burning the law?

The reason for passing the Stamp Act was more about Parliament showing Colonial Americans "who was in charge" and less about collecting a tax on stamp-act goods. Did the Members of Parliament achieve their objective?

Benjamin Franklin's partner, David Hall, found a way to print the news without subjecting his newspaper to a stamp-act tax. In doing so, he "got around the law." Was that a good or a bad thing? Explain your answer.

Media Credits

Image, entitled “Burning of Stamp Act, Boston,” online courtesy Library of Congress. Color-film copy transparency LC-USZC4-1583. Created in 1903 and based on an earlier German production from:

“Six scenes of a twelve-scene set picturing events of the American Revolution.” Creator 1: Daniel Nickolaus Chodowiecki. Creator 1 dates: 1726-1801. Creator 1 role: engraver.

Source creator: Sprengel, M.C. (Matthias Christian), 1746-1803. Source Title: Allgemeines historisches Taschenbuch oder Abriss der merkwürdigsten neuen Welt-Begebenheiten enthaltend für 1784 die Geschichte der Revolution von NordAmerica.

Source place of publication: Berlin. Source publisher: bey Haude und Spener.

Original Source date: [1784].

PD