Isaac Newton, the towering seventeenth-century genius, started his life as a tiny baby who (according to his mother) could have fit inside a quart mug. That’s because he was born, very prematurely, when he entered the world on January 4, 1643.

When he was young, he loved to build models. One of his best was a tiny mill which actually could grind flour. How was it powered? By a mouse, running inside a wheel.

While in his twenties, after receiving his degree from Trinity College (at Cambridge University), Isaac had to return home. School was closed, because of the plague which had descended on England in 1665-66.

Home for Newton, at that time, was his Mother’s house - known as Woolsthorpe Manor - in Lincolnshire. Among other things, Woolsthorpe featured a garden with a “Flower of Kent” apple tree.

Even though Cambridge remained closed for a time, Newton continued to work at home. Later in his life, he called this period away from the University as “the prime of my age for invention.”

One day at Woolsthorpe, as the story goes, Newton was thinking about the apples growing in his Mother’s garden. He wondered why they always fell straight to the ground (instead of falling in some other direction). He reasoned that there was some type of force making the apples fall as they did.

We call this force “gravity.”

Is the apple story true? Is it just a fanciful legend? What is its source?

London’s Royal Society, where Newton once worked, has an original manuscript - now digitized with page-turning capability - which helps us answer those questions. It is William Stukeley’s 1752 Memoirs of Sir Isaac Newton's Life.

On page 15, of that manuscript, we read Stukeley’s story about the apple incident (split into paragraphs, here, for easier reading):

After dinner, the weather being warm, we went into the garden, & drank tea under the shade of some apple trees, only he, & myself. amidst other discourse, he told me, he was just in the same situation, as when formerly, the notion of gravitation came into his mind.

“Why should that apple always descend perpendicularly to the ground,” thought he to him self: occasion’d by the fall of an apple, as he sat in a contemplative mood: “Why should it not go sideways, or upwards? but constantly to the earths centre?

Assuredly, the reason is, that the earth draws it. There must be a drawing power in matter. & the sum of the drawing power in the matter of the earth must be in the earths centre, not in any side of the earth. therefore dos [does] this apple fall perpendicularly, or toward the centre.

If matter thus draws matter; it must be in proportion of its quantity. Therefore the apple draws the earth, as well as the earth draws the apple.”

So ... one source of the apple story comes from Newton’s biographer. Is there any other source?

Newton also told the story to John Conduitt, his assistant at the Royal Mint. Married to Newton’s niece, Catherine Barton, Conduitt recalled what his uncle told him:

In the year 1666 he retired again from Cambridge to his mother in Lincolnshire. Whilst he was pensively meandering in a garden it came into his thought that the power of gravity (which brought an apple from a tree to the ground) was not limited to a certain distance from Earth, but that this power must extend much further than was usually thought.

“Why not as high as the Moon,” said he to himself, “& if so, that must influence her motion & perhaps retain her orbit,” whereupon he fell a calculating what would be the effect of that supposition.

“The effect of that supposition” was, in fact, a world-changing event. As one of NASA’s Apollo 8 crew members put it (on returning to Earth after orbiting the Moon in December of 1968:

I think Isaac Newton is doing most of the driving now. (See NASA’s account of Apollo 8, including this comment by Bill Anders, Mission Commander.)

Media Credits

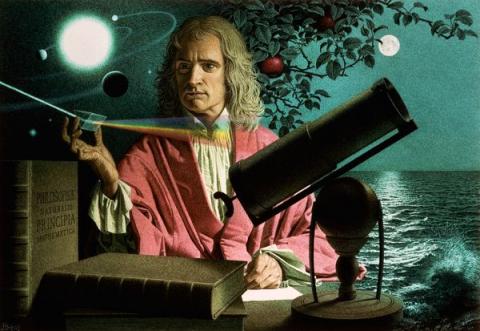

Artist's conception of Isaac Newton—with some of the items he used, influenced or thought-about surrounding him—online via Wikimedia Commons.