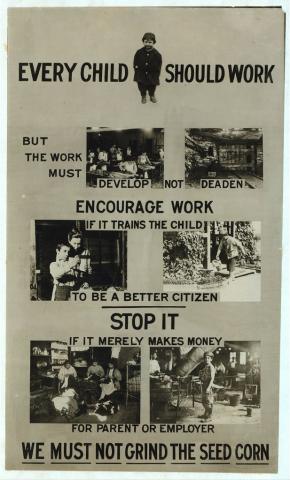

This poster image is believed to be a photo taken by Lewis Hine, circa 1914. Hine (1874-1940) photographed American child laborers, between 1908-1918, on behalf of the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC). In 1954, the NCLC gave its records—including Hine’s 5,000 photos (approximately) and 350 negatives—to the Library of Congress. The gift included these specific instructions: “There will be no restrictions of any kind on your use of the Hine photographic material.” Image online via the National Child Labor Committee collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

As the industrial revolution took hold in 19th century America, factory owners preferred to hire families, including children. Child labor was accepted and widespread in the early years of that century; no one clamored for its abolition. (Even Andrew Carnegie—who would later become the richest man in the world—started his working career as a "bobbin boy" in a Pittsburgh textile mill.)

When long workdays prevented children from getting even a modest education, however, people began to get concerned:

- An 1813 law, passed in Connecticut, encouraged employers to provide young workers with lessons in reading, writing and arithmetic. It did little good.

- In 1836, Massachusetts passed America's first child labor law. It required children under the age of 15 to spend at least three months a year in school.

After the Civil War was over (in 1865), a highly mechanized textile industry flourished in the South. With the slaves freed, children were brought into the shops:

- Children as young as 6 or 7 worked 13-hour days in hot, dusty mills and factories. Proposals for change were unwelcome.

- At the dawn of the 20th century, only a few Southern states had passed laws limiting the numbers of hours children could work.

During the first year of the 20th century, America's census revealed a disturbing fact. At least 2 million children were working in mines, mills, farms, factories, stores and on city streets.

Charles Dickens—an Englishman forced to work at Warren's Blacking Factory when he was a lad of twelve—had written numerous novels, such as Oliver Twist, which drew attention to the plight of 19th century working children. Dickens and his stories—including A Christmas Carol—remain popular today and were helpful in calling attention to the travails of working-class children in Britain.

Few protections, however, were in place for American children by the time of the 1900 census.

Back

Back

Next Chapter

Next Chapter

Back

Back

Next Chapter

Next Chapter